Maintaining Intangible Cultural Assets

Dialects are by no means hotchpotches of random “false” deviations from a standard language. On the contrary, dialects are language systems in their own right, out of which over the centuries standard languages have evolved.

Thus dialect vocabularies are of great importance for the past and the present of the German language as a whole.

Dialect use is an expression, a mirror even, of lifestyle at home and at work, of customs and ways of thought, indeed the entire political, intellectual and cultural history of a speech community. Against this background, vernaculars count among the most precious cultural assets we know. The research and documentation in large-scale philological dialect dictionaries is indispensable for a region’s cultural memory and for the preservation of its specific use of living language.

Geographical and Historical Scope

The area covered by the Bayerisches Wörterbuch comprises Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria, the Upper Palatinate and neighbouring regions of Bavarian Swabia, Middle Franconia and Upper Franconia. Over and above the vernaculars spoken today, Bavaria’s literary tradition since its beginnings in the 8th century is also taken into account.

Entire Range of Bavarian Vernacular – including Phrases and Proverbs

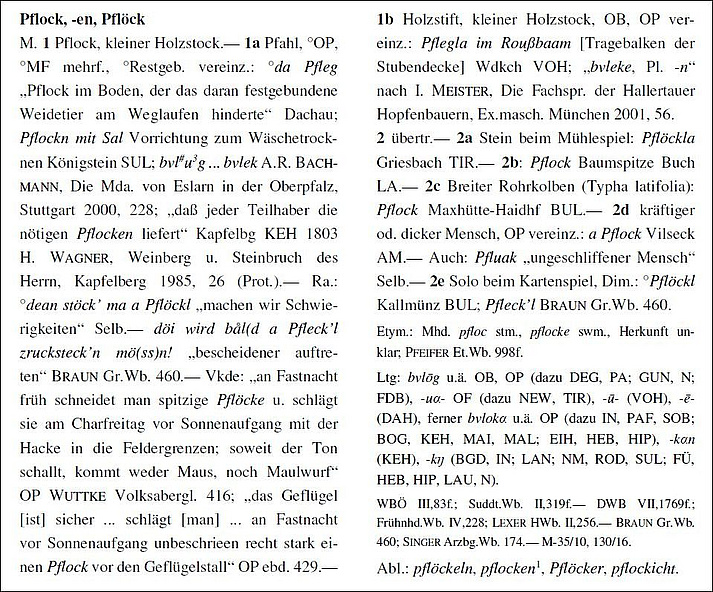

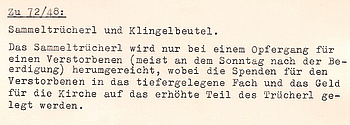

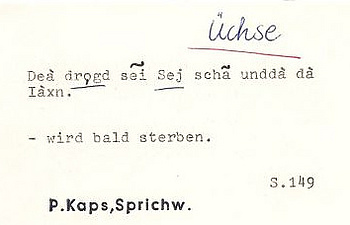

The Bayerisches Wörterbuch elaborates the exact meaning of words in their historic development and current geographical distribution. To this end, examples of oral and written usage are documented, including turns of phrase, comparisons, proverbs and riddles. Text examples from literary sources and from ordinary everyday spoken language offer lively illustrations of words’ meanings and use within a sentence. Where necessary, ethnological and ontological information and details of pronunciation and word origin are appended.

What the Words Mean

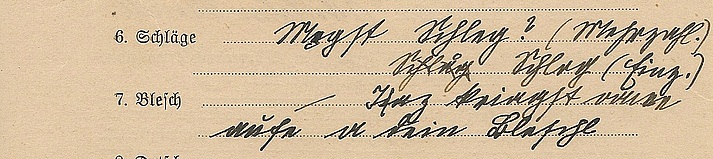

A word and a meaning are very rarely a one-to-one match. The lively, colourful usages typical of dialects may express a certain meaning in many different ways, by using terms that perhaps differ only in the nuance. Bavarian, for example, has several terms for the meaning “tongue” (Zunge), among them Blätsche, Bläuel, Bleck, Blecker, Breitling, Plapper, Plärrel, Plempel, Plesche, Pleschel, Pleschling, Plettel, Pletter, Läsche, Lätsche, Lecker, Lell, Leller, Schläpper, and also numerous further figurative terms such as (Spül)Lumpen, Rüssel, Schlecker.

On the other hand, a single word may have numerous different meanings: in Haunzenbergersöll (Altlandkreis Vilsbiburg) the word Pleschel means ‘Schläge’ (beating); in Lauterhofen (Neumarkt) this word stands for ‘eitrige Blase oder Rufe’ (suppurating blister); more widely known are the meanings ‘großer, starker Mensch’ (big, strong person), ‘schwerfälliger Mensch’ (ponderous person), ‘clumsy person’. Pleschel is also often used for a body part: in Starnberg one can say: Der ko mit seim Bleschl d’Stubn z’sammkehrn, referring to someone’s gift of the gab, in Seeon (Traunstein) Bleschl refers to “Lippe” (lip) and in Ettal (Garmisch) if you say: hau ihm doch oane auf sein Bleschl! (why don’t you slap him!), you are referirng to the mouth pars pro toto for the whole face.

Other meanings recorded are the crest of a cock, a jug, and as a general denotation of a large object.

Playing with Words

What would a language be like if it did not include playful elements? That is why, in its account of the Bavarian vernacular, the Bayerisches Wörterbuch also documents proverbs, idioms, verses and puns. The Dictionary of Bavarian Dialects also registers humorous terms, tongue twisters and so called “Schnaderhüpfel”, a special verse form known throughout the German-speaking Alpine Region. The Schnaderhüpfel is an often improvised, four-line stanza, sung in the specific three-quarter tact of a “Gstanzl”. The Schnaderhüpfel is sometimes sung as dialogue, the couplet of one singer being answered by the couplet of another. The content is predominantly witty, but can sometimes be quite darkly humorous, and is typically used to entertain people at big events like weddings etc.

Words and their History

Over the course of time, words may change their pronunciation and their meaning. When historians, members of the judiciary, anthropologists and others interested in Bavaria’s history want to read and understand written sources from the past, they need explanations of old word forms and meanings.

A people that cannot understand its own old written testimonies loses their own history.

Since the history of the German language largely consists of the history of German regional languages, regional dictionaries with interpretations of historic word forms naturally represent indispensable basic works.

This is why the Bayerische Wörterbuch presents the change of words and their meanings over the course of time, starting with the beginning of written records in the 8th century.

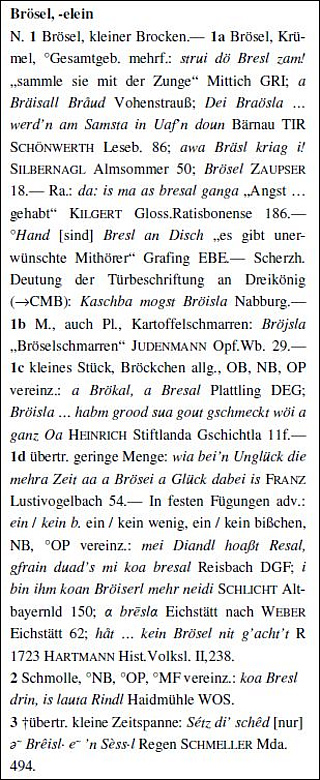

So you can learn that in the 14th century Botung meant ‘Anordnung, Befehl’ (order) and Brösel (crumbs) in the 19th century or Fahrt (ride) in the 17th century actually stood for ‘kleine Zeitspanne, Weile’ (short time, little while).

What Do We Learn from Dictionary Articles?

Each dictionary article offers a treasure of information on a specific word:

- its meanings

- in which regions those meanings are found

- how the word is used in a sentence

- in which contexts the word is found (constructions, proverbs, verses, sayings, country lore)

- the word’s origin

- how the word is pronounced in different regions (phonetic transcription)

- grammatical information, e.g. part of speech, gender of nouns, etc.

- ethnological and ontological background

- references to treatments of the same word in the most important dictionaries and grammars